Upper body

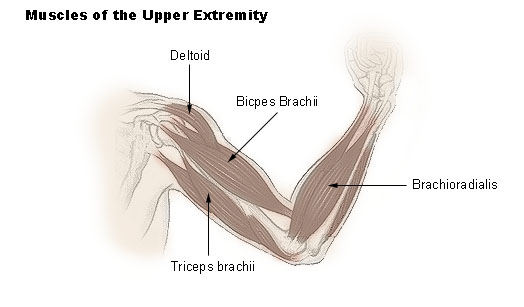

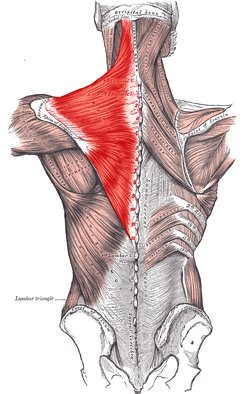

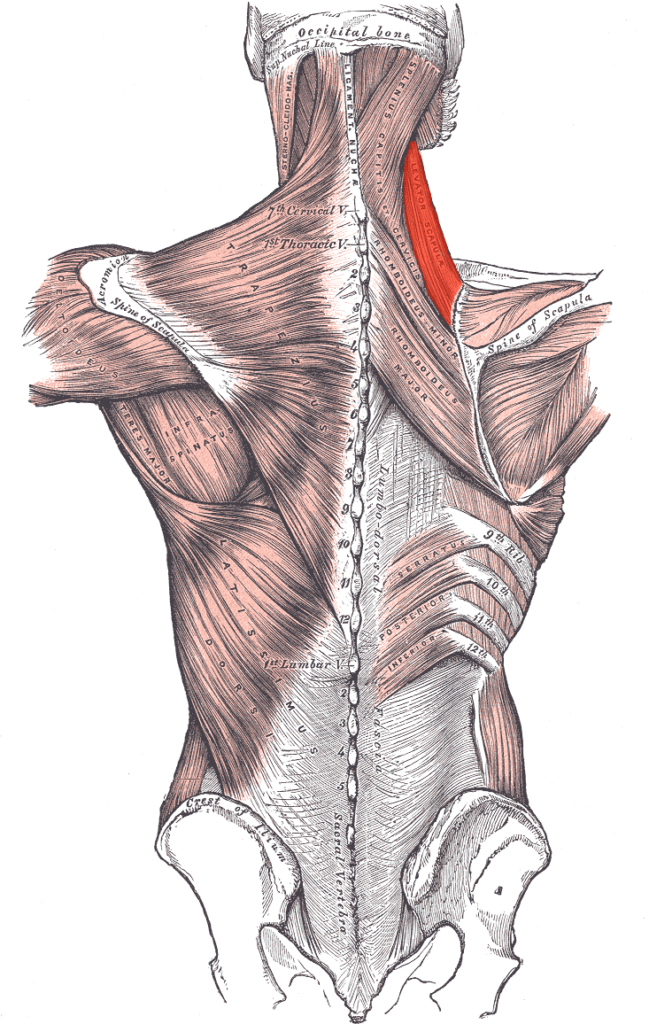

The upper body comprises a complex network of muscles responsible for a wide range of movements, stability, and strength. Key muscle groups include the pectorals (chest), deltoids (shoulders), latissimus dorsi (back), and the muscles of the arms, such as the biceps and triceps. However, beyond these more prominent muscles, there are several smaller, often neglected muscles that play critical roles in upper body function. These include the serratus anterior, which aids in scapular movement and stability; the rotator cuff muscles (supraspinatus, infraspinatus, teres minor, subscapularis), which are essential for shoulder stability and injury prevention; and the rhomboids and lower trapezius, which contribute to proper posture and scapular retraction. The brachialis and brachioradialis are crucial for elbow flexion but are frequently overshadowed by the biceps. Neglecting these smaller muscles can lead to imbalances, reduced functional strength, and a higher risk of injury, highlighting the importance of a balanced approach to upper body training.

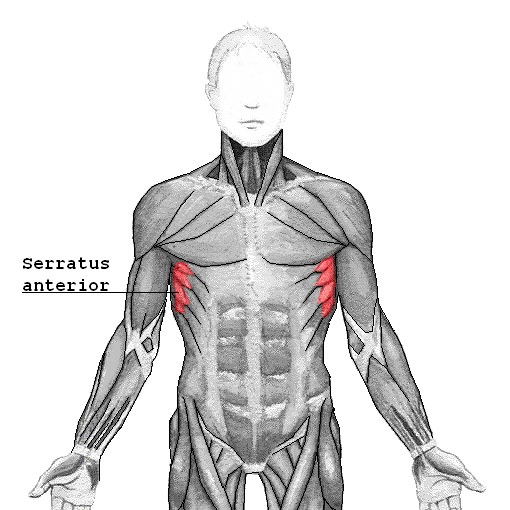

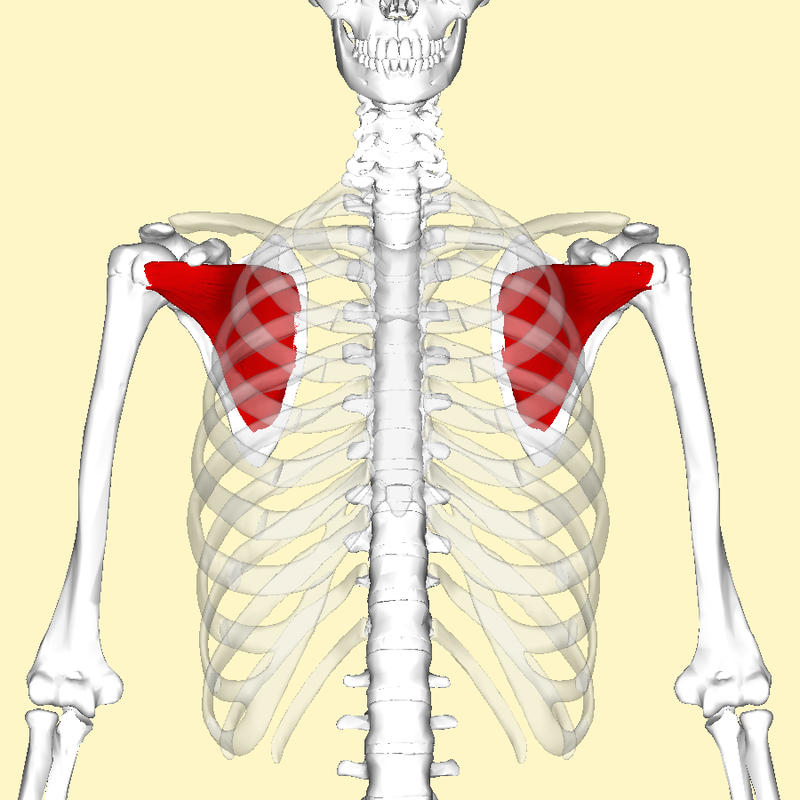

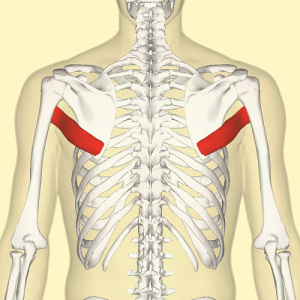

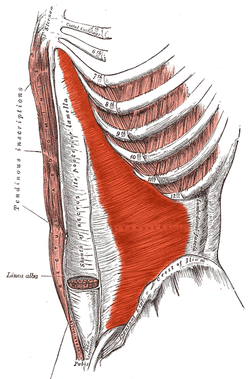

Serratus anterior

The serratus anterior is a crucial yet often underappreciated muscle that plays a vital role in the movement and stability of the scapula (shoulder blade). Located on the side of the chest, beneath the pectoral muscles, the serratus anterior originates on the upper ribs and inserts along the medial border of the scapula. Its primary function is to protract the scapula, allowing for forward movement of the shoulder, which is essential in actions such as pushing and punching. Additionally, it assists in upward rotation of the scapula, which is important during overhead activities. A well-functioning serratus anterior stabilizes the scapula against the rib cage, preventing winging of the scapula, a condition that can lead to shoulder dysfunction and pain. Despite its importance, the serratus anterior is often overlooked in traditional strength training routines, leading to potential imbalances and compromised shoulder mechanics. Strengthening this muscle can improve overall shoulder stability, enhance performance in pressing movements, and reduce the risk of shoulder injuries.

A highly effective exercise that specifically targets the serratus anterior is the Scapular Push-Up. Here’s how to perform it:

1. Starting Position: Begin in a standard push-up position, with your hands placed slightly wider than shoulder-width apart and your body forming a straight line from head to heels. Your arms should be fully extended, with your elbows locked.

2. Movement: Instead of bending your elbows as you would in a regular push-up, keep your arms straight and focus on moving your shoulder blades. Lower your body slightly by retracting your shoulder blades (bringing them together), and then push through your hands to protract your shoulder blades (moving them apart) as far as possible. This pushing motion should cause your upper back to round slightly at the top of the movement.

3. Contraction: At the top of the movement, focus on squeezing and engaging the serratus anterior by fully extending your arms and pushing your shoulder blades forward.

4. Repetition: Lower your body back to the starting position by retracting the shoulder blades and repeat the movement for the desired number of repetitions.

The scapular push-up is excellent for strengthening the serratus anterior, as it isolates this muscle and trains it to function properly during shoulder movements, enhancing stability and reducing the risk of shoulder injuries.

Rotator Cuff Muscles

The rotator cuff is a group of four small yet vital muscles—supraspinatus, infraspinatus, teres minor, and subscapularis—that play a crucial role in shoulder stability and movement. These muscles originate on the scapula (shoulder blade) and attach to the humerus (upper arm bone), forming a cuff around the shoulder joint. Each muscle has a specific function: the supraspinatus aids in lifting the arm away from the body (abduction), the infraspinatus and teres minor are responsible for external rotation of the arm, and the subscapularis controls internal rotation. Together, these muscles work to stabilize the shoulder joint by keeping the head of the humerus securely within the shallow socket of the scapula during arm movements. Despite their importance, the rotator cuff muscles are often neglected in traditional strength training routines, which typically emphasize larger, more visible muscles like the deltoids and pectorals. Neglecting these muscles can lead to imbalances, reduced shoulder stability, and an increased risk of injuries such as rotator cuff tears or impingement. Incorporating exercises that specifically target the rotator cuff is essential for maintaining shoulder health, improving functional strength, and preventing injury.

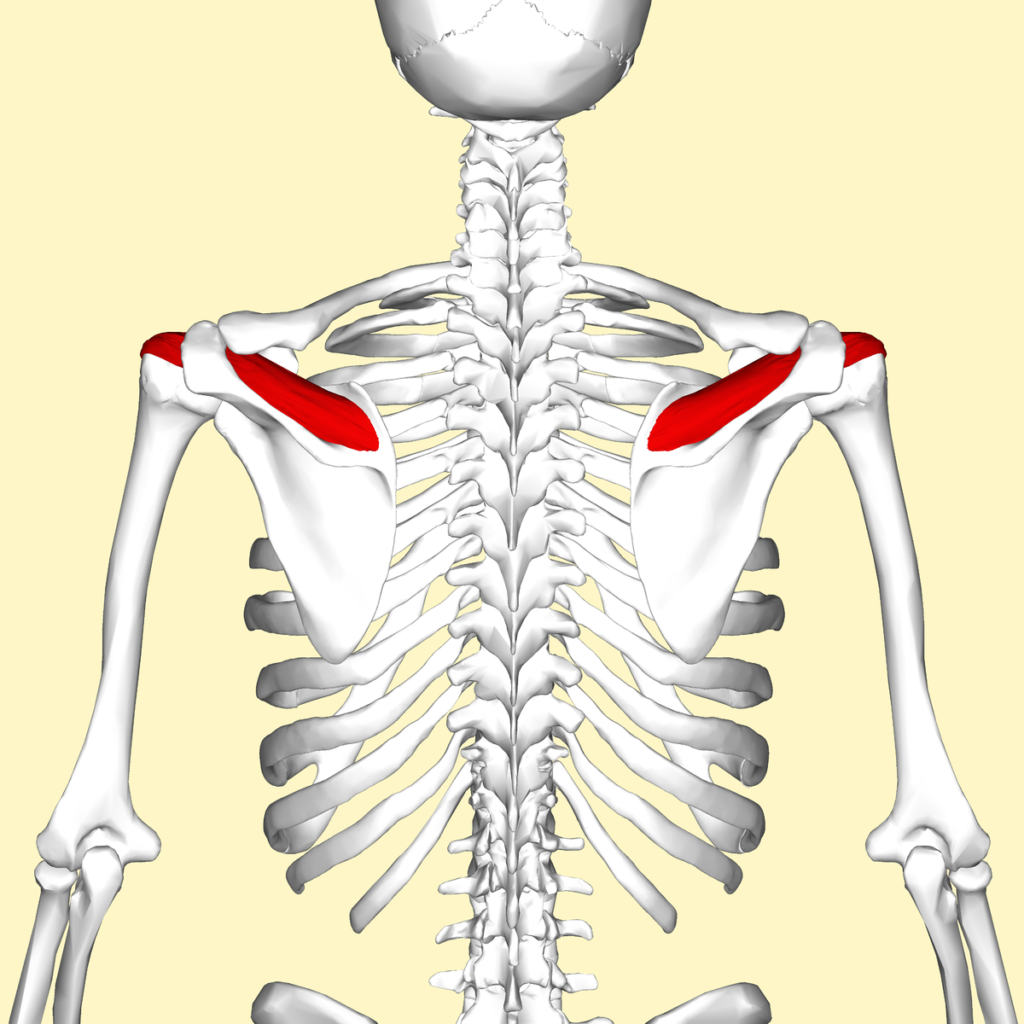

Supraspinatus

The supraspinatus is one of the four rotator cuff muscles, playing a key role in shoulder stability and movement. It is located in the supraspinous fossa, a small depression on the upper part of the scapula, and runs underneath the acromion (part of the shoulder blade), attaching to the top of the humerus (upper arm bone). The primary function of the supraspinatus is to initiate abduction of the arm—lifting it away from the body—especially during the first 15 degrees of movement, after which the deltoid muscle takes over. Additionally, the supraspinatus helps stabilize the shoulder joint by holding the head of the humerus firmly within the shallow socket of the scapula, preventing dislocation during various arm movements. Despite its critical function, the supraspinatus is prone to injury due to its location and the high demands placed on it, particularly in repetitive overhead activities such as throwing, swimming, or lifting. Weakness or injury in the supraspinatus can lead to shoulder pain, reduced range of motion, and compromised shoulder stability. Therefore, exercises that strengthen the supraspinatus are crucial for maintaining shoulder health, preventing injuries, and ensuring optimal performance in activities requiring arm elevation.

A highly effective exercise that specifically targets the supraspinatus is the Prone Shoulder Abduction. Here’s how to perform it:

1. Starting Position: Lie face down on a flat bench with your arms hanging straight down towards the floor, palms facing inward. You can hold light dumbbells or simply use your body weight if you’re just starting.

2. Movement: With your arm fully extended, slowly raise it laterally (to the side) until it is level with your shoulder, forming a “T” shape with your body. Make sure to keep your thumb pointing upward throughout the movement to ensure the supraspinatus is properly engaged.

3. Contraction: At the top of the movement, pause for a moment and squeeze your shoulder blades together to fully engage the supraspinatus.

4. Return: Slowly lower your arm back to the starting position with control, resisting the weight as you return.

5. Repetition: Repeat the movement for the desired number of repetitions before switching to the other arm.

The prone shoulder abduction is particularly effective for isolating and strengthening the supraspinatus, as it works the muscle in its primary function of initiating shoulder abduction. This exercise helps to build strength and stability in the shoulder, reducing the risk of rotator cuff injuries.

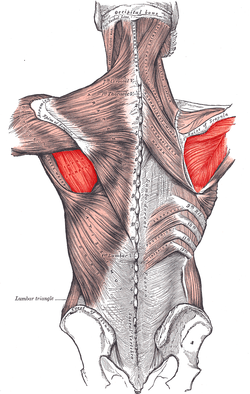

Infraspinatus

The infraspinatus is a key muscle of the rotator cuff, crucial for shoulder function and stability. It is located on the back of the shoulder, occupying the infraspinous fossa of the scapula, and extends laterally to attach to the greater tubercle of the humerus (upper arm bone). The infraspinatus is primarily responsible for external rotation of the arm, allowing the hand to turn outward. This movement is essential in many daily activities and sports, such as throwing, swinging a racket, or performing overhead lifts. Additionally, the infraspinatus contributes to stabilizing the shoulder joint by keeping the head of the humerus firmly in place within the socket during arm movements. Due to its specific role in external rotation, the infraspinatus is often underdeveloped compared to more prominent shoulder muscles like the deltoids, leading to imbalances that can predispose the shoulder to injuries such as impingement or rotator cuff tears. Strengthening the infraspinatus is vital for maintaining balanced shoulder mechanics, enhancing performance in activities that involve arm rotation, and preventing shoulder dysfunction.

An effective exercise that specifically targets the infraspinatus is the Side-Lying External Rotation. Here’s how to perform it:

1. Starting Position: Lie on your side on a flat surface or bench, with your upper arm resting along your side and your elbow bent at a 90-degree angle. Keep your elbow tucked into your side, and let your forearm rest across your abdomen. You can hold a light dumbbell in your hand or use a resistance band if you’re just starting.

2. Movement: Keeping your elbow fixed against your side, slowly rotate your forearm upward, lifting the dumbbell or band against the resistance. This external rotation movement engages the infraspinatus, which is responsible for rotating the arm outward.

3. Contraction: At the top of the movement, when your forearm is parallel to the floor, pause and squeeze the infraspinatus to maximize contraction.

4. Return: Slowly lower your forearm back to the starting position, resisting the weight as you return.

5. Repetition: Perform the desired number of repetitions on one side before switching to the other arm.

The side-lying external rotation is particularly effective for isolating and strengthening the infraspinatus, which is crucial for shoulder stability and injury prevention. This exercise is commonly used in rehabilitation programs to address shoulder imbalances and improve rotator cuff function.

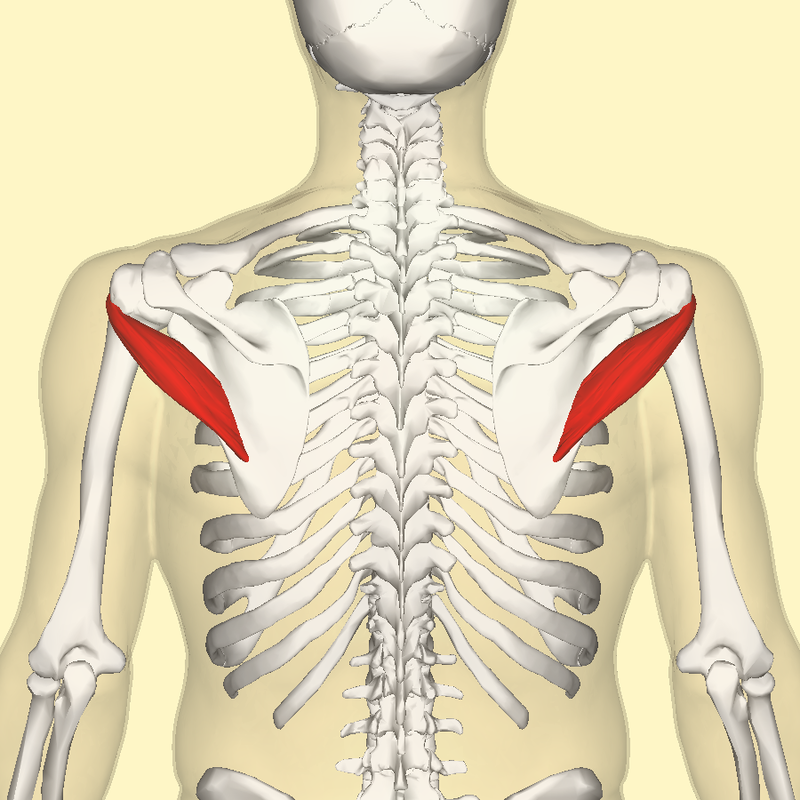

Teres Minor

The teres minor is a small but essential muscle of the rotator cuff, contributing significantly to shoulder stability and movement. Located on the back of the shoulder, it originates from the lateral border of the scapula and attaches to the greater tubercle of the humerus (upper arm bone). The primary function of the teres minor is to assist in the external rotation of the arm, similar to the infraspinatus, and to help with the adduction (bringing the arm toward the body) of the shoulder. This muscle also plays a crucial role in stabilizing the shoulder joint by helping to hold the head of the humerus in the glenoid cavity of the scapula during various arm movements. Despite its important function, the teres minor is often overlooked in traditional shoulder workouts, leading to potential imbalances and increased risk of shoulder injuries. Strengthening the teres minor can improve shoulder mobility, enhance performance in activities requiring external rotation, and contribute to overall shoulder joint health by ensuring balanced muscle development and stability.

An effective exercise that specifically targets the teres minor is the Standing External Rotation with a Resistance Band. Here’s how to perform it:

1. Starting Position: Attach a resistance band to a sturdy anchor point at about elbow height. Stand sideways to the anchor point, with the side you want to work facing the anchor. Hold the free end of the band in the hand of the arm closest to the anchor. Your elbow should be bent at a 90-degree angle, with your forearm across your abdomen.

2. Movement: Keeping your elbow tucked into your side, slowly rotate your forearm outward, away from your body, against the resistance of the band. This external rotation movement directly engages the teres minor, which is responsible for rotating the arm outward.

3. Contraction: Continue rotating until your forearm is in line with your torso, feeling the contraction in the back of your shoulder.

4. Return: Slowly bring your arm back to the starting position, controlling the movement and resisting the pull of the band.

5. Repetition: Perform the desired number of repetitions before switching sides to work the opposite teres minor.

This standing external rotation exercise effectively isolates the teres minor, helping to strengthen and stabilize the shoulder joint. It is particularly beneficial for improving shoulder function and preventing injuries related to the rotator cuff.

Subscapularis

The subscapularis is the largest and strongest muscle of the rotator cuff, playing a crucial role in shoulder stability and movement. Located on the anterior (front) surface of the scapula, within the subscapular fossa, this muscle extends across the shoulder joint to attach to the lesser tubercle of the humerus (upper arm bone). The primary function of the subscapularis is to facilitate internal rotation of the arm, allowing movements such as bringing the hand toward the body or reaching behind the back. Additionally, it helps with shoulder adduction (pulling the arm toward the body) and extension (moving the arm backward). Importantly, the subscapularis provides significant stability to the shoulder joint by holding the head of the humerus securely within the shallow socket of the scapula, particularly during lifting and pushing movements. Despite its importance, the subscapularis is often undertrained, as traditional shoulder exercises tend to focus more on the external rotators and larger, more visible muscles. Weakness or imbalance in the subscapularis can lead to shoulder instability and increase the risk of rotator cuff injuries. Strengthening the subscapularis is essential for maintaining balanced shoulder function, preventing injuries, and supporting overall upper body strength and mobility.

An effective exercise that specifically targets the subscapularis is the Internal Rotation with a Resistance Band. Here’s how to perform it:

1. Starting Position: Attach a resistance band to a sturdy anchor point at about elbow height. Stand sideways to the anchor point, with the side you want to work facing away from the anchor. Hold the free end of the band in the hand of the arm furthest from the anchor. Your elbow should be bent at a 90-degree angle, with your forearm parallel to the floor and positioned outward from your body.

2. Movement: Keeping your elbow tucked into your side, slowly rotate your forearm inward, pulling the band across your body. This internal rotation movement directly engages the subscapularis, which is responsible for rotating the arm inward.

3. Contraction: As you rotate your arm inward, focus on squeezing the subscapularis at the end of the movement, when your forearm is across your abdomen.

4. Return: Slowly allow your arm to return to the starting position, controlling the movement and resisting the pull of the band.

5. Repetition: Perform the desired number of repetitions before switching sides to work the opposite subscapularis.

This internal rotation exercise is excellent for isolating and strengthening the subscapularis, which is a key muscle in stabilizing the shoulder joint and ensuring smooth internal rotation of the arm. Strengthening the subscapularis helps prevent shoulder injuries, especially in activities that involve repetitive internal rotation, such as throwing or swimming.

Brachialis

The brachialis is a key muscle located in the upper arm, lying beneath the biceps brachii, and plays a crucial role in elbow flexion. Unlike the biceps, which assist in both elbow flexion and forearm supination (rotating the forearm to turn the palm upward), the brachialis is solely responsible for flexing the elbow, regardless of the position of the forearm. This makes it a powerful and essential muscle for movements that involve bending the arm, such as lifting and pulling. The brachialis originates on the lower half of the humerus and attaches to the coronoid process of the ulna, the bone on the inner side of the forearm. Despite its significant role in arm strength, the brachialis is often overlooked in traditional upper arm workouts, which tend to focus on the more prominent biceps. However, developing the brachialis can lead to greater overall arm strength and a fuller appearance of the upper arm by pushing the biceps outward, creating a more pronounced arm contour. Strengthening the brachialis not only enhances functional strength but also contributes to a balanced and aesthetically pleasing upper arm.

An effective exercise that specifically targets the brachialis is the Hammer Curl. Here’s how to perform it:

1. Starting Position: Stand with your feet shoulder-width apart, holding a pair of dumbbells with your arms fully extended by your sides. Your palms should face each other in a neutral grip, with the thumbs pointing upward.

2. Movement: Keeping your upper arms stationary, slowly curl the dumbbells toward your shoulders by bending your elbows. Focus on lifting the weights using your brachialis, which lies underneath the biceps.

3. Contraction: At the top of the movement, when the dumbbells are near your shoulders, squeeze your brachialis to maximize contraction.

4. Return: Slowly lower the dumbbells back to the starting position, fully extending your arms while maintaining control over the weights.

5. Repetition: Perform the desired number of repetitions, ensuring that you maintain a steady, controlled movement throughout the exercise.

The hammer curl is particularly effective for targeting the brachialis because it minimizes the involvement of the biceps brachii, placing more emphasis on the brachialis muscle. Strengthening the brachialis helps increase arm strength and adds size to the upper arm, as this muscle is crucial for elbow flexion.

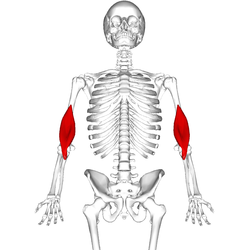

Brachioradialis

The brachioradialis is a prominent muscle of the forearm that plays a key role in flexing the elbow, particularly when the forearm is in a neutral position, such as during a handshake. It originates on the lateral ridge of the humerus, just above the elbow, and runs along the forearm to insert at the styloid process of the radius, one of the two main bones of the forearm. Unlike the biceps, which is more active during supination (palm-up movements), the brachioradialis is most engaged during movements where the forearm is in a neutral or slightly pronated position (palm facing down). This muscle is often underemphasized in traditional arm workouts, which typically focus on the biceps and triceps. However, the brachioradialis is crucial for balanced arm strength and functional grip, as it helps stabilize the forearm during lifting and pulling activities. Strengthening the brachioradialis not only enhances overall forearm development and grip strength but also contributes to more efficient and injury-resistant elbow and wrist function, making it an important muscle for both athletes and those engaged in manual labor.

An effective exercise that specifically targets the brachioradialis is the Reverse Curl. Here’s how to perform it:

1. Starting Position: Stand with your feet shoulder-width apart, holding a pair of dumbbells or a barbell with an overhand grip (palms facing down). Your arms should be fully extended, with the weights resting against your thighs.

2. Movement: Keeping your upper arms stationary and close to your body, slowly curl the weights upward by bending your elbows. Focus on lifting the weights primarily using the brachioradialis, which is responsible for flexing the elbow when the forearm is in a pronated (palm-down) position.

3. Contraction: At the top of the movement, when the weights are near your shoulders, pause and squeeze the brachioradialis to enhance the muscle contraction.

4. Return: Slowly lower the weights back to the starting position, fully extending your arms while maintaining control over the movement.

5. Repetition: Perform the desired number of repetitions, ensuring that your movements remain smooth and controlled throughout the exercise.

The reverse curl is highly effective for isolating the brachioradialis because the overhand grip minimizes the involvement of the biceps brachii, shifting the focus to the brachioradialis. Strengthening this muscle not only improves forearm strength but also contributes to overall arm size and grip strength, which is beneficial for various lifting and pulling activities.

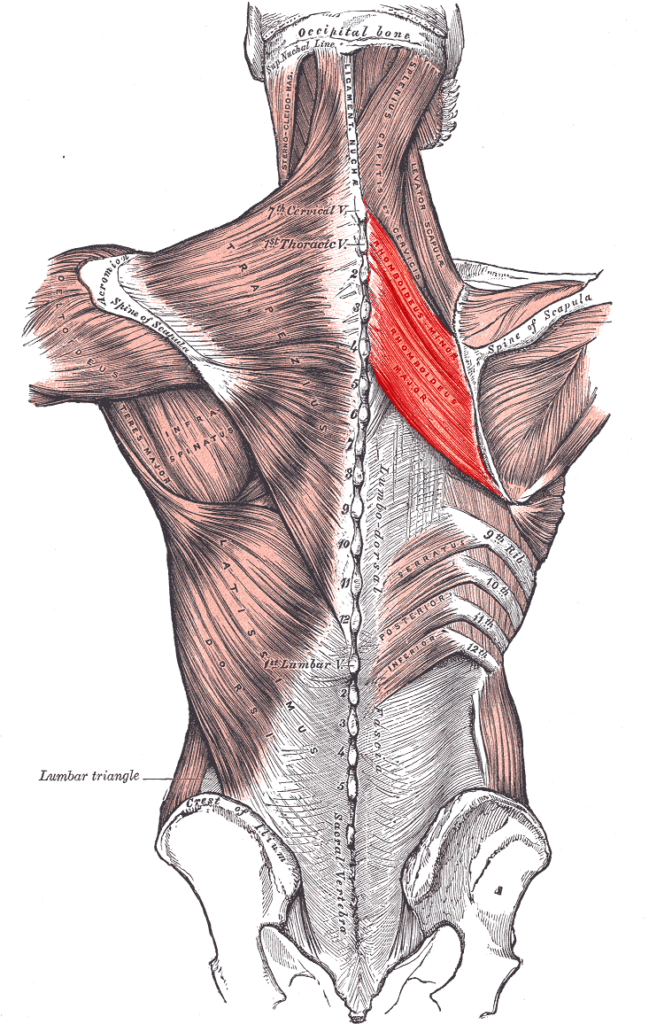

Rhomboids

The rhomboids, consisting of the rhomboid major and rhomboid minor, are two important muscles located in the upper back, playing a crucial role in scapular (shoulder blade) movement and stability. These muscles originate from the spinal vertebrae (C7 to T5) and insert into the medial border of the scapula. The primary function of the rhomboids is to retract the scapula, pulling the shoulder blades toward the spine, which is essential for maintaining good posture and proper shoulder alignment. Additionally, they assist in downward rotation of the scapula, a movement important in actions such as pulling or rowing. Despite their importance, the rhomboids are often overlooked in traditional back workouts, which tend to focus more on the larger, more superficial muscles like the latissimus dorsi. Neglecting the rhomboids can lead to rounded shoulders, poor posture, and an increased risk of shoulder injuries due to imbalances in the upper back and shoulder girdle. Strengthening the rhomboids not only improves posture and shoulder stability but also enhances the overall function and aesthetics of the upper back, making these muscles essential for balanced upper body development.

Major rhomboids

The rhomboid major is a key muscle in the upper back that plays a vital role in scapular retraction, posture, and shoulder stability. This muscle originates from the spinous processes of the thoracic vertebrae T2 to T5 and inserts into the medial border of the scapula, specifically from the spine of the scapula down to its inferior angle. The primary function of the rhomboid major is to retract the scapula, pulling the shoulder blades toward the spine, which is essential for maintaining an upright posture and ensuring proper alignment of the shoulders. Additionally, it assists in the downward rotation of the scapula, which is important during movements such as pulling and rowing. Despite its importance, the rhomboid major is often undertrained in traditional back routines that focus more on larger muscles like the latissimus dorsi. Neglecting the rhomboid major can lead to muscle imbalances, poor posture, and increased risk of shoulder injuries due to weakened scapular support. Strengthening the rhomboid major is crucial for enhancing upper back strength, improving posture, and maintaining the overall health and stability of the shoulder girdle.

An effective exercise that specifically targets the rhomboid major is the Face Pull. Here’s how to perform it:

1. Starting Position: Attach a resistance band or cable to an anchor point at approximately face height. Stand facing the anchor point, holding the handles or ends of the band with both hands, using an overhand grip (palms facing downward). Step back until there is tension in the band or cable, and position your feet shoulder-width apart.

2. Movement: With your arms extended in front of you, pull the band or cable directly toward your face, focusing on squeezing your shoulder blades together. Your elbows should flare out to the sides, creating a 90-degree angle at the shoulder joint as you pull.

3. Contraction: As you pull the band or cable toward your face, concentrate on contracting the rhomboid major by bringing your shoulder blades as close together as possible. Hold this contracted position for a moment.

4. Return: Slowly extend your arms, allowing the band or cable to return to the starting position with control, while maintaining tension in your upper back.

5. Repetition: Perform the desired number of repetitions, ensuring that each movement is controlled and focused on engaging the rhomboid major.

The face pull is particularly effective for targeting the rhomboid major because it emphasizes scapular retraction, the primary function of this muscle. Regularly incorporating face pulls into your routine can improve posture, enhance upper back strength, and reduce the risk of shoulder injuries by promoting balanced development of the upper back muscles.

Minor rhomboids

The rhomboid minor is a small but important muscle located in the upper back, just above the rhomboid major. It originates from the spinous processes of the C7 and T1 vertebrae and inserts into the medial border of the scapula, near the spine of the scapula. Despite its smaller size, the rhomboid minor plays a crucial role in scapular retraction, pulling the shoulder blades toward the spine, and contributing to overall upper back stability and posture. In addition to retraction, the rhomboid minor assists in the downward rotation of the scapula, a movement necessary during pulling motions and activities that involve lifting. Although it is often overshadowed by larger muscles in the back, the rhomboid minor is essential for maintaining proper shoulder alignment and posture. Neglecting this muscle can lead to shoulder imbalances, poor posture, and an increased risk of injury, especially in the shoulder and upper back region. Strengthening the rhomboid minor can significantly improve scapular stability, enhance posture, and contribute to a more balanced and functional upper back.

An effective exercise that targets the rhomboid minor specifically is the Prone Y-Raise. Here’s how to perform it:

1. Starting Position: Lie face down on a bench or stability ball with your arms extended straight in front of you, forming a “Y” shape with your body. Your thumbs should be pointing up towards the ceiling, and your head should be in a neutral position, aligned with your spine.

2. Movement: With your arms straight and elbows slightly bent, slowly lift your arms upward toward the ceiling, focusing on squeezing your shoulder blades together as you raise your arms. This movement directly engages the rhomboid minor, which is responsible for retracting and stabilizing the scapula.

3. Contraction: At the top of the movement, when your arms are fully raised, hold the position for a moment, emphasizing the contraction in the rhomboid minor.

4. Return: Slowly lower your arms back to the starting position with control, resisting the urge to let them drop quickly.

5. Repetition: Perform the desired number of repetitions, maintaining control and focus on the rhomboid minor throughout the exercise.

The prone Y-raise is particularly effective for targeting the rhomboid minor because it isolates the muscles involved in scapular retraction and stabilization. By regularly incorporating this exercise into your routine, you can improve shoulder stability, enhance upper back strength, and contribute to better posture, reducing the risk of shoulder and neck discomfort.

Lower Trapezius

The lower trapezius is a critical muscle located in the lower portion of the trapezius muscle, extending from the middle to the lower thoracic vertebrae (T4 to T12) to the spine of the scapula. This muscle plays a key role in the downward movement and stabilization of the scapula, as well as assisting in the upward rotation of the scapula during overhead motions. The lower trapezius is essential for maintaining proper shoulder alignment and posture, particularly by counterbalancing the often overactive upper trapezius, which can lead to muscle imbalances if not properly addressed. Despite its importance, the lower trapezius is frequently neglected in traditional upper body workouts, which tend to focus on more prominent muscles like the upper trapezius and deltoids. This neglect can result in poor posture, shoulder impingement, and an increased risk of injury, particularly in the shoulder and neck regions. Strengthening the lower trapezius is vital for achieving a balanced upper body, improving shoulder mechanics, and supporting functional movements, especially those involving lifting or reaching overhead.

An effective exercise that specifically targets the lower trapezius is the Prone Y-Raise. Here’s how to perform it:

1. Starting Position: Lie face down on a bench, stability ball, or an incline bench set at a low angle. Let your arms hang down toward the floor, with your thumbs pointing upward. Your body should be in a straight line, and your head should be in a neutral position, aligned with your spine.

2. Movement: With your arms straight and elbows slightly bent, slowly lift your arms upward and slightly outward to form a “Y” shape with your body. As you lift your arms, focus on pulling your shoulder blades down and together, engaging the lower trapezius muscle.

3. Contraction: At the top of the movement, when your arms are fully raised, pause and squeeze the lower trapezius, emphasizing the downward and inward pull of your shoulder blades.

4. Return: Slowly lower your arms back to the starting position with control, maintaining tension in your back muscles throughout the movement.

5. Repetition: Perform the desired number of repetitions, ensuring each movement is slow, controlled, and focused on engaging the lower trapezius.

The prone Y-raise is particularly effective for isolating and strengthening the lower trapezius because it emphasizes the muscle’s role in scapular depression and retraction. Strengthening the lower trapezius helps improve shoulder stability, posture, and overall upper back strength, reducing the risk of shoulder impingement and other upper body injuries.

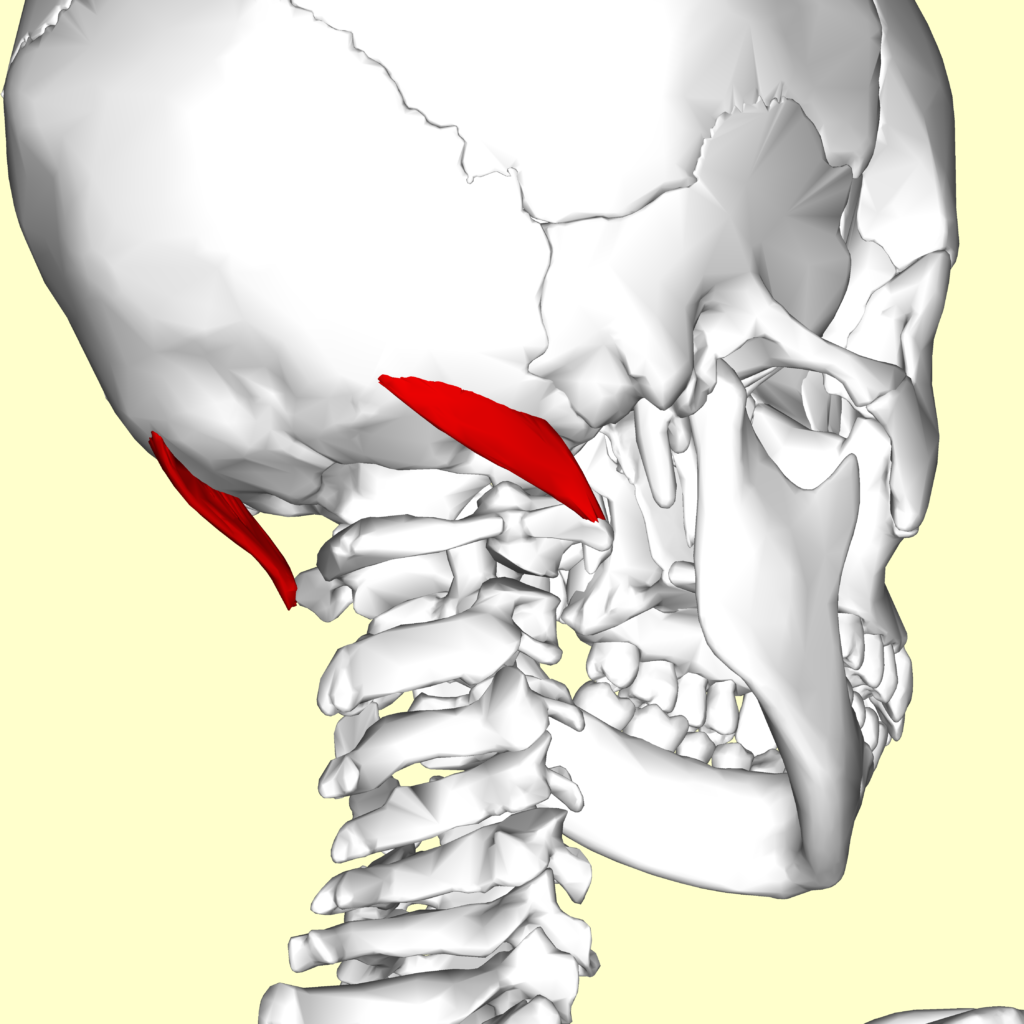

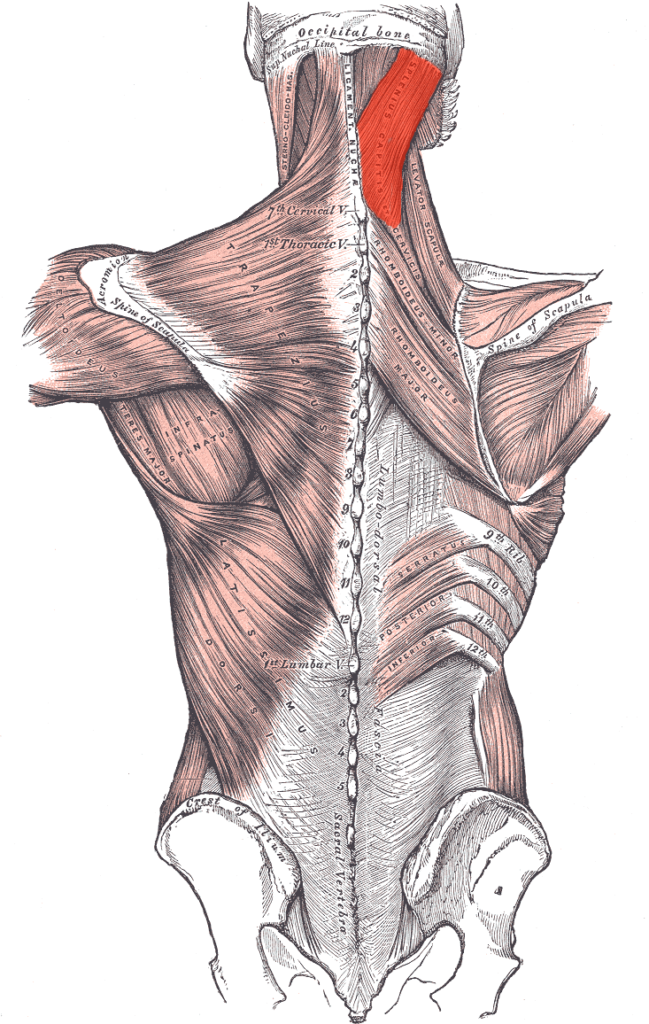

Levator Scapulae

The levator scapulae is a slender, elongated muscle located at the back and side of the neck, playing a crucial role in the movement and stabilization of the scapula (shoulder blade). It originates from the transverse processes of the upper four cervical vertebrae (C1 to C4) and inserts into the superior part of the medial border of the scapula. The primary function of the levator scapulae is to elevate the scapula, allowing for shoulder shrugging and assisting in tilting the scapula downward during certain arm movements. Additionally, it helps in rotating the neck and contributes to maintaining proper head posture. Despite its important functions, the levator scapulae is often overlooked in traditional strength training routines, leading to potential imbalances and neck or shoulder discomfort, especially in individuals with poor posture or those who engage in repetitive overhead activities. Tightness or weakness in this muscle can contribute to neck pain, stiffness, and tension headaches. Strengthening and properly stretching the levator scapulae is essential for maintaining healthy neck and shoulder mechanics, reducing the risk of upper body discomfort, and enhancing overall posture and functional movement.

An effective exercise that specifically targets the levator scapulae is the Dumbbell Shrug with a Slight Head Tilt. Here’s how to perform it:

1. Starting Position: Stand upright with your feet shoulder-width apart, holding a pair of dumbbells at your sides with your palms facing your body. Keep your shoulders relaxed and your arms fully extended.

2. Head Position: Tilt your head slightly to one side (toward one shoulder) to lengthen the levator scapulae on the opposite side. This head position helps isolate the levator scapulae during the exercise.

3. Movement: Slowly shrug your shoulders upward toward your ears, focusing on the side where the levator scapulae is lengthened. As you lift your shoulders, avoid using your arms to help, and focus on using the muscles in your neck and upper back.

4. Contraction: At the top of the movement, when your shoulders are as close to your ears as possible, hold the position for a moment and squeeze the levator scapulae to maximize contraction.

5. Return: Slowly lower your shoulders back to the starting position with control, keeping the tension in the levator scapulae.

6. Repetition: Perform the desired number of repetitions on one side, then switch the head tilt and repeat the exercise for the opposite levator scapulae.

The dumbbell shrug with a slight head tilt is particularly effective for targeting the levator scapulae because it isolates the muscle by minimizing the involvement of other muscles in the shoulder area. This exercise helps improve neck and shoulder strength, reduces tension, and can help alleviate discomfort or tightness in the upper back and neck region.

Teres Major

The teres major is a small but powerful muscle located in the upper back, just below the shoulder joint, playing an essential role in the movement and stability of the arm. It originates from the lower part of the lateral border of the scapula and inserts into the medial lip of the intertubercular sulcus of the humerus (upper arm bone). The primary functions of the teres major include internal rotation, adduction, and extension of the arm, which are important for movements such as pulling, lifting, and rotating the arm inward. Often referred to as the “little lat” because of its similar function to the latissimus dorsi, the teres major assists in stabilizing the shoulder joint during these actions. Despite its important role, the teres major is frequently overshadowed by larger muscles like the latissimus dorsi and pectorals in traditional upper body workouts. Neglecting the teres major can lead to imbalances in shoulder strength and mobility, potentially increasing the risk of injury during activities that require strong and coordinated arm movements. Strengthening the teres major is crucial for enhancing shoulder stability, improving the range of motion, and supporting overall upper body strength and function.

An effective exercise that specifically targets the teres major is the Single-Arm Dumbbell Row with an Emphasis on Extension. Here’s how to perform it:

1. Starting Position: Stand next to a bench, placing one knee and the same-side hand on the bench for support. Your back should be flat, and your other foot should be firmly planted on the ground. Hold a dumbbell in your free hand with your arm extended straight down toward the floor.

2. Movement: Begin by pulling the dumbbell upward toward your hip, leading with your elbow while keeping your arm close to your body. Focus on using the teres major to initiate the movement by drawing your upper arm backward in an extended arc.

3. Contraction: As you pull the dumbbell up, bring your elbow slightly past your torso and squeeze the muscles in your upper back, particularly the teres major. Hold this position for a brief moment to maximize muscle contraction.

4. Return: Slowly lower the dumbbell back to the starting position, fully extending your arm while maintaining control over the movement.

5. Repetition: Perform the desired number of repetitions on one side, then switch to the other arm and repeat.

The single-arm dumbbell row with an emphasis on extension is particularly effective for isolating the teres major, as it focuses on shoulder extension and adduction, which are the primary functions of this muscle. Strengthening the teres major helps improve overall shoulder stability, enhances upper back strength, and contributes to a more balanced and well-developed upper body.

Pectoralis Minor

The pectoralis minor is a small, triangular muscle located underneath the larger pectoralis major in the chest, playing a crucial role in the movement and stabilization of the scapula (shoulder blade). It originates from the third, fourth, and fifth ribs near their junction with the costal cartilages and inserts into the coracoid process of the scapula. The primary functions of the pectoralis minor include protracting the scapula, pulling it forward and downward, and stabilizing the scapula against the thoracic wall. This muscle is particularly important during movements such as reaching forward, pushing, and stabilizing the shoulder girdle during upper body exercises. Despite its vital role in shoulder mechanics, the pectoralis minor is often overlooked in traditional chest workouts, which typically focus on the more visible pectoralis major. When the pectoralis minor becomes tight or overactive, it can contribute to poor posture, rounded shoulders, and shoulder impingement. Strengthening and properly stretching the pectoralis minor are essential for maintaining healthy shoulder alignment, improving posture, and preventing upper body discomfort and injuries, especially in those who frequently engage in pushing activities or desk work.

An effective exercise that specifically targets the pectoralis minor is the Incline Push-Up Plus. Here’s how to perform it:

1. Starting Position: Set up an incline by placing your hands on a bench, step, or sturdy platform that is about knee to waist height. Position your hands slightly wider than shoulder-width apart, with your body forming a straight line from your head to your heels. Your arms should be fully extended, and your shoulders relaxed.

2. Movement: Lower your chest toward the bench by bending your elbows, performing a standard push-up. As you push back up to the starting position, add an extra movement by actively pushing your shoulders forward and allowing your upper back to round slightly. This “plus” movement involves protracting the shoulder blades, which specifically engages the pectoralis minor.

3. Contraction: Focus on contracting the pectoralis minor as you push your shoulders forward during the “plus” part of the movement. This action helps to isolate and strengthen the muscle.

4. Return: After completing the protraction, return your shoulders to their neutral position and repeat the entire push-up movement.

5. Repetition: Perform the desired number of repetitions, ensuring that each push-up includes the “plus” movement to fully engage the pectoralis minor.

The incline push-up plus is particularly effective for targeting the pectoralis minor because the added scapular protraction directly activates this muscle, which is responsible for moving the scapula forward and downward. Strengthening the pectoralis minor can help improve shoulder stability, enhance posture, and reduce the risk of shoulder impingement or other upper body injuries.

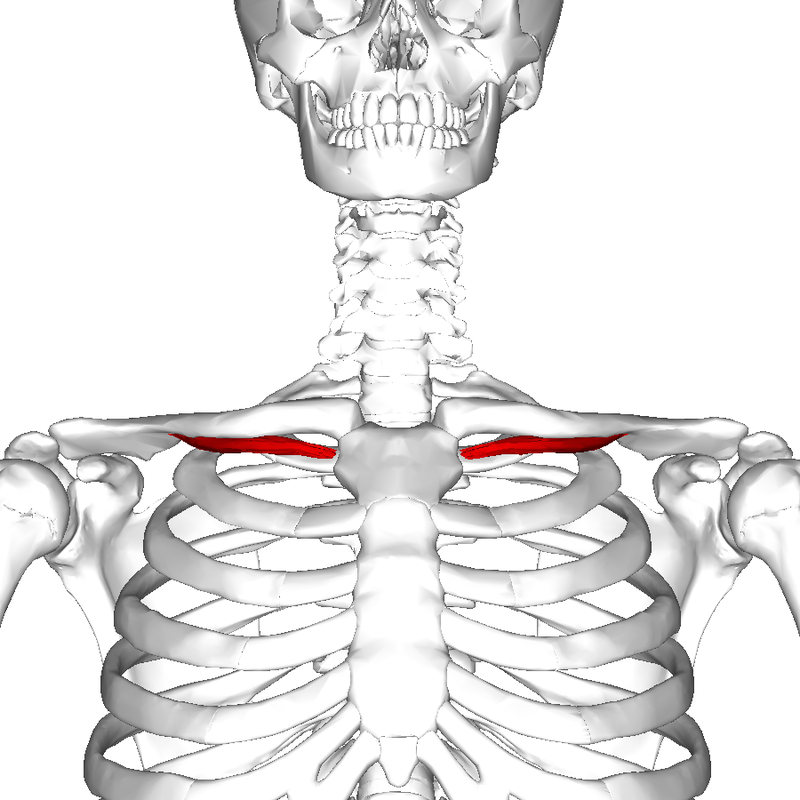

Subclavius

The subclavius is a small, yet significant muscle located beneath the clavicle (collarbone), running horizontally from the first rib to the underside of the clavicle. Despite its modest size, the subclavius plays a crucial role in stabilizing the clavicle, especially during movements of the shoulder and arm. This muscle acts to depress the clavicle, pulling it downward and forward, which helps protect the sternoclavicular joint (where the clavicle meets the sternum) and contributes to the overall stability of the shoulder girdle. The subclavius also helps absorb shock and impact forces that might otherwise be transmitted directly to the clavicle, reducing the risk of fractures. However, the subclavius is often overlooked in both fitness routines and anatomical discussions, as it is a deep muscle that doesn’t contribute directly to visible muscle mass or strength. Tightness or dysfunction in the subclavius can contribute to shoulder pain or reduced range of motion, particularly in activities that involve extensive arm movement or overhead lifting. Properly maintaining the subclavius through targeted stretching and strengthening can enhance shoulder stability, improve posture, and reduce the risk of injury in the upper body.

An effective exercise that specifically targets the subclavius is the Subclavius Stretch with Resistance Band Activation. This exercise focuses on both stretching and activating the subclavius muscle. Here’s how to perform it:

1. Starting Position: Attach a resistance band to a sturdy anchor point at about chest height. Stand facing away from the anchor, holding the band in one hand with your arm extended straight forward at shoulder height. Your palm should face downward.

2. Movement (Stretch and Activation): Begin by taking a small step forward to create slight tension in the band, then gently tilt your head away from the arm holding the band. This stretches the subclavius muscle.

3. Activation: While maintaining the stretch, slightly pull the band downward and across your body at a diagonal angle, as if trying to bring your hand toward the opposite hip. Focus on using the subclavius to initiate this movement, which engages the muscle by stabilizing the clavicle.

4. Contraction: Hold the position briefly at the end of the movement, feeling the tension in the subclavius as it works to stabilize the shoulder.

5. Return: Slowly release the tension by bringing your arm back to the starting position and relaxing your head.

6. Repetition: Perform the desired number of repetitions, then switch to the other arm to work the subclavius on the opposite side.

This exercise targets the subclavius by combining a gentle stretch with activation of the muscle as it stabilizes the clavicle. While the subclavius is a small and often overlooked muscle, strengthening it can help improve shoulder stability and prevent issues related to clavicle movement, especially in activities that involve pushing or overhead movements.

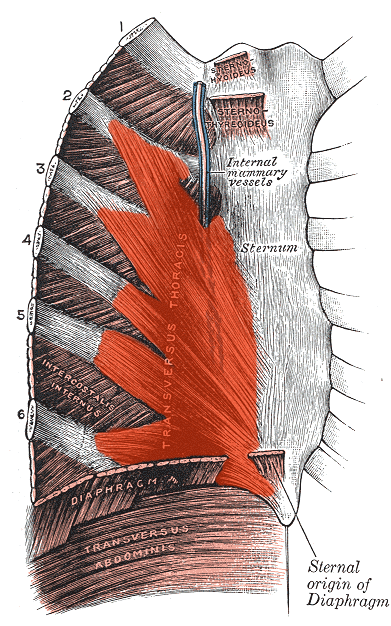

Infrasternal Angle Muscles

The infrasternal angle muscles, primarily including the transversus thoracis, play an essential role in respiratory mechanics and core stability. Located on the inside of the anterior chest wall, the transversus thoracis originates from the posterior surface of the lower part of the sternum and inserts into the inner surfaces of the costal cartilages of the second to sixth ribs. These muscles help depress the ribs during forced expiration, such as when blowing out air forcefully or during vigorous physical activity, aiding in the expulsion of air from the lungs. Although these muscles are not directly involved in the more visible aspects of core strength or muscle mass, they contribute to the overall stability of the thoracic region, influencing posture and the effectiveness of breathing patterns. The infrasternal angle muscles are often overlooked in traditional fitness routines, which typically emphasize more prominent abdominal muscles. However, strengthening and maintaining the flexibility of these muscles are crucial for efficient respiratory function, improved core stability, and maintaining proper ribcage positioning, which can impact overall posture and physical performance. Neglecting these muscles may lead to dysfunctional breathing patterns and imbalances in the core, making them important to consider in a comprehensive fitness program.

Transversus Thoracis

The transversus thoracis is a thin, flat muscle located on the inner surface of the anterior chest wall, playing an important role in respiratory function. It originates from the posterior surface of the lower part of the sternum and the xiphoid process, extending laterally to attach to the inner surfaces of the costal cartilages of the second to sixth ribs. The primary function of the transversus thoracis is to assist in depressing the ribs during forced expiration, such as during heavy breathing, coughing, or blowing out air forcefully. By pulling the rib cage downward, this muscle helps reduce the volume of the thoracic cavity, facilitating the expulsion of air from the lungs. Despite its critical role in the mechanics of breathing, the transversus thoracis is often overlooked in discussions of core and respiratory muscles, as it is not involved in the more visible aspects of muscle strength or body contour. However, maintaining the strength and flexibility of the transversus thoracis is essential for efficient respiratory function, particularly during intense physical activities that demand rapid and forceful breathing. Additionally, its role in stabilizing the ribcage contributes to overall thoracic stability, which is important for proper posture and the function of other core muscles. Neglecting this muscle may lead to less efficient breathing and potential imbalances in the chest wall, making it a valuable component of a comprehensive fitness and respiratory health program.

An effective exercise that specifically targets the transversus thoracis is the Deep Breathing with Resistance (Respiratory Muscle Training). This exercise focuses on engaging the transversus thoracis, a muscle involved in the forced expiration of air from the lungs. Here’s how to perform it:

1. Starting Position: Sit or stand in a comfortable position with your spine straight. Place a resistance band or a hand on your chest to provide light pressure and feedback.

2. Movement (Inhalation): Begin by taking a deep breath in through your nose, allowing your chest and ribs to expand outward as you fill your lungs with air. Focus on keeping your shoulders relaxed and letting the movement come from your chest.

3. Movement (Exhalation): As you exhale through your mouth, engage the transversus thoracis by actively pulling your ribs downward and inward. This action should feel like you are trying to forcefully expel the air from your lungs, which engages the transversus thoracis muscle. You can apply gentle pressure with your hands or resistance band to provide additional resistance during the exhalation.

4. Contraction: Focus on fully contracting the transversus thoracis as you complete the exhalation, ensuring that your ribs move downward and inward.

5. Repetition: Repeat the breathing cycle for the desired number of repetitions, concentrating on the active engagement of the transversus thoracis during each exhalation.

This deep breathing exercise with resistance is particularly effective for targeting the transversus thoracis because it directly involves the muscle in its primary function—assisting with forced exhalation and stabilizing the ribcage. Strengthening the transversus thoracis through respiratory muscle training can improve breathing efficiency, enhance respiratory function, and support the overall stability of the thoracic region. This exercise is especially beneficial for athletes, singers, or individuals looking to improve their respiratory health and core stability.

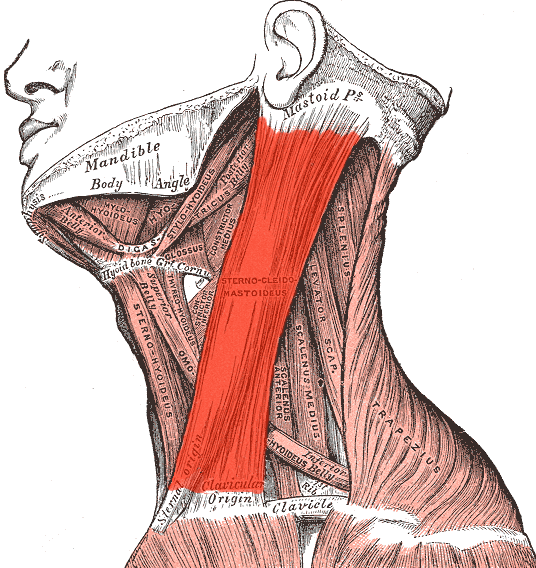

Sternocleidomastoid

The sternocleidomastoid (SCM) is a prominent and powerful muscle in the neck that plays a crucial role in head and neck movement, as well as in maintaining posture. It originates from two points: the manubrium of the sternum and the medial portion of the clavicle, and it inserts into the mastoid process of the temporal bone of the skull, just behind the ear. The primary functions of the sternocleidomastoid are to rotate the head to the opposite side, tilt it toward the same side, and flex the neck forward, such as when nodding or bringing the chin to the chest. Additionally, when both sternocleidomastoid muscles work together, they can elevate the sternum and clavicle, assisting in deep breathing by increasing the volume of the thoracic cavity. Despite its importance in head and neck mobility, the SCM is often overlooked in strength and conditioning routines, leading to potential imbalances, tightness, and discomfort, especially for those who spend long hours in static positions, such as sitting at a desk. Properly stretching and strengthening the sternocleidomastoid is essential for maintaining neck flexibility, preventing tension headaches, and promoting good posture. Neglecting this muscle can contribute to neck pain, reduced range of motion, and imbalances that affect overall upper body alignment.

An effective exercise that specifically targets the sternocleidomastoid (SCM) is the Neck Flexion with Resistance. This exercise helps strengthen the SCM, which is responsible for flexing and rotating the neck. Here’s how to perform it:

1. Starting Position: Lie on your back on a flat surface, such as a bench or mat, with your head hanging slightly off the edge. Keep your knees bent and feet flat on the floor for stability. Place a small, soft weight (such as a rolled-up towel, small medicine ball, or light resistance band) on your forehead for resistance.

2. Movement: Begin by slowly tucking your chin toward your chest, flexing your neck forward. Focus on engaging the sternocleidomastoid muscles on both sides of your neck as you lift your head toward your chest.

3. Contraction: Hold the top position for a moment, fully engaging the SCM, and ensure your movement is controlled and deliberate.

4. Return: Slowly lower your head back to the starting position, allowing your neck to extend gently while maintaining control.

5. Repetition: Perform the desired number of repetitions, ensuring that each movement is slow and controlled to effectively target the sternocleidomastoid.

For added difficulty, you can increase the resistance by using a slightly heavier weight or by performing the exercise with a resistance band. This exercise is particularly effective for strengthening the SCM, improving neck stability, and enhancing posture, especially for those who spend long hours in forward head positions, such as working at a desk or using electronic devices. Properly strengthening the SCM can also help alleviate neck pain and tension.

Core and midsection

The core and midsection are fundamental areas of the body that play a crucial role in almost every movement, providing stability, balance, and strength. The core is not limited to the visible “six-pack” muscles, or rectus abdominis, but also includes deeper muscles like the transverse abdominis, internal and external obliques, multifidus, and muscles of the pelvic floor. These muscles work together to stabilize the spine, support posture, and facilitate movements like twisting, bending, and lifting. The transverse abdominis acts as a natural corset, providing deep core stability, while the obliques are essential for trunk rotation and lateral flexion. The multifidus and pelvic floor muscles contribute to spinal support and stability, particularly during dynamic movements. A strong and well-conditioned core is vital not only for athletic performance but also for everyday activities, as it helps protect the spine, improve balance, and prevent injuries. However, traditional fitness routines often focus only on the superficial abdominal muscles, neglecting the deeper core muscles that are crucial for true functional strength. Comprehensive core training that targets all these muscles is essential for maintaining a healthy, resilient body, capable of handling the demands of both daily life and athletic endeavors.

Transverse Abdominis

The transverse abdominis (TVA) is the deepest layer of the abdominal muscles, playing a vital role in core stability and overall trunk support. Unlike the more superficial rectus abdominis, which is responsible for the visible “six-pack,” the transverse abdominis wraps around the torso horizontally, like a natural corset. It originates from the lower ribs, thoracolumbar fascia, iliac crest, and inguinal ligament, and inserts into the linea alba and pubic crest. The primary function of the transverse abdominis is to compress the abdominal contents, which stabilizes the spine and pelvis during movement. This stabilization is essential for maintaining posture, protecting the lower back, and ensuring efficient movement patterns during both everyday activities and more intense physical exertion. Activating the TVA creates intra-abdominal pressure, which acts as a supportive brace for the lower back, reducing the risk of injury, especially during heavy lifting or dynamic sports. Despite its critical role in core function, the transverse abdominis is often neglected in traditional ab workouts, which tend to focus more on the superficial muscles. Strengthening the TVA through targeted exercises, such as planks and abdominal bracing, is essential for developing a strong, stable core that enhances overall performance and reduces the risk of lower back pain and injury.

An effective exercise that specifically targets the transverse abdominis (TVA) is the Vacuum Exercise (Stomach Vacuum). This exercise focuses on engaging and strengthening the deepest layer of the abdominal muscles. Here’s how to perform it:

1. Starting Position: You can perform this exercise in a standing, sitting, or kneeling position, or even lying down on your back. Start by ensuring your spine is in a neutral position, with your shoulders relaxed and your chest lifted slightly.

2. Movement (Exhalation): Begin by taking a deep breath in through your nose, filling your lungs with air and allowing your abdomen to expand naturally.

3. Contraction (Vacuum): As you exhale slowly through your mouth, draw your belly button inward toward your spine, pulling your abdominal wall in as tightly as possible. Imagine you are trying to make your waist as small as possible. This action engages the transverse abdominis, which acts like a natural corset around your waist.

4. Hold: Hold the vacuum position for 10 to 20 seconds while continuing to breathe lightly. Keep the rest of your body relaxed and focus on maintaining the tension in your core.

5. Return: After holding the contraction, relax your abdominal muscles and return to the starting position.

6. Repetition: Perform several repetitions, gradually increasing the hold time as your TVA strength improves.

The vacuum exercise is particularly effective for targeting the transverse abdominis because it emphasizes the muscle’s role in stabilizing the core and drawing the abdominal wall inward. Regular practice of this exercise can improve core stability, enhance posture, and contribute to a slimmer waistline by strengthening the deep core muscles that support the spine and internal organs. It is a foundational exercise often used in both fitness and rehabilitation programs to improve core function and reduce the risk of lower back pain.

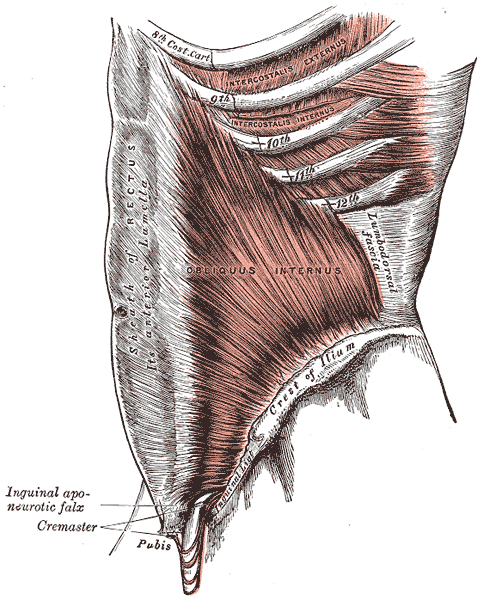

Internal Obliques

The internal obliques are a crucial component of the core musculature, located deep within the abdominal wall beneath the external obliques. These muscles originate from the iliac crest, thoracolumbar fascia, and inguinal ligament, and they insert into the lower ribs and the linea alba, a fibrous structure that runs down the midline of the abdomen. The internal obliques play a key role in trunk rotation, lateral flexion (bending sideways), and in stabilizing the spine and pelvis during movement. They work in concert with the external obliques, but in the opposite direction, creating a powerful mechanism for twisting motions, such as those needed in sports like tennis or golf. Additionally, the internal obliques assist in compressing the abdominal contents, contributing to intra-abdominal pressure that supports the lower back and improves posture. Despite their importance, the internal obliques are often undertrained in conventional core workouts, which tend to focus more on the rectus abdominis and superficial obliques. Targeting the internal obliques through rotational exercises, side planks, and other movements that emphasize twisting and lateral bending is essential for a well-rounded core, enhancing both functional strength and stability, and reducing the risk of injury in the lower back and hips.

An effective exercise that specifically targets the internal obliques is the Side Plank with Hip Dips. Here’s how to perform it:

1. Starting Position: Begin by lying on your side with your legs extended and stacked on top of each other. Place your forearm on the ground directly beneath your shoulder, with your elbow bent at a 90-degree angle. Your body should form a straight line from head to heels.

2. Movement (Side Plank): Engage your core muscles, including the internal obliques, and lift your hips off the ground so that your body forms a straight line from shoulders to ankles. Keep your top hand either on your hip or extended upward toward the ceiling for balance.

3. Hip Dips: From the side plank position, slowly lower your hip toward the floor without touching it, then lift your hip back up to the starting position. Focus on engaging the internal obliques on the side closest to the floor as you perform this dipping motion.

4. Contraction: At the top of each lift, squeeze the internal obliques to maximize muscle engagement. Maintain a steady, controlled movement throughout the exercise.

5. Repetition: Perform the desired number of repetitions on one side, then switch to the other side and repeat.

The side plank with hip dips is particularly effective for targeting the internal obliques because it challenges these muscles to stabilize the body and control lateral movement. This exercise not only strengthens the internal obliques but also improves overall core stability, enhances balance, and supports better posture. By regularly incorporating this exercise into your routine, you can develop stronger, more resilient internal obliques, which play a key role in trunk rotation, lateral flexion, and maintaining a stable core during various activities.

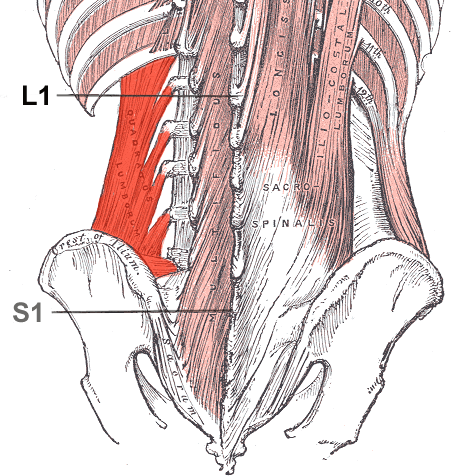

Quadratus Lumborum

The quadratus lumborum (QL) is a deep muscle in the lower back that plays a vital role in stabilizing the spine and supporting the pelvis. It originates from the iliac crest (the top of the hip bone) and the iliolumbar ligament and inserts into the 12th rib and the transverse processes of the lumbar vertebrae. The quadratus lumborum is primarily responsible for lateral flexion of the spine, allowing you to bend to the side, as well as extending the lumbar spine when both sides contract simultaneously. Additionally, it helps stabilize the pelvis and lower back during activities such as walking, running, and lifting, making it crucial for maintaining proper posture and alignment. The QL also plays a significant role in respiration by anchoring the 12th rib during deep inhalation, aiding in the mechanics of breathing. Despite its importance, the quadratus lumborum is often overlooked in traditional workout routines, which can lead to imbalances and contribute to lower back pain or discomfort, especially in those who sit for prolonged periods or perform repetitive bending motions. Strengthening and stretching the quadratus lumborum through targeted exercises like side planks, hip hikes, and specific stretches can enhance spinal stability, improve core strength, and reduce the risk of lower back injuries, making it an essential muscle for both functional movement and overall back health.

An effective exercise that specifically targets the quadratus lumborum (QL) is the Side Bridge (Side Plank) with Leg Lift. Here’s how to perform it:

1. Starting Position: Begin by lying on your side with your legs extended and stacked on top of each other. Place your forearm on the ground directly beneath your shoulder, with your elbow bent at a 90-degree angle. Your body should form a straight line from head to heels.

2. Movement (Side Plank): Engage your core and lift your hips off the ground so that your body forms a straight line from shoulders to ankles. Your opposite arm can be extended toward the ceiling or placed on your hip for balance.

3. Leg Lift: Once you are stable in the side plank position, lift your top leg upward, maintaining the alignment of your body. This movement increases the demand on the quadratus lumborum as it works to stabilize your body and keep your hips from dropping.

4. Contraction: As you lift your leg, focus on engaging the quadratus lumborum on the side closest to the floor. Hold the leg lift for a moment at the top, then slowly lower your leg back to the starting position while maintaining the side plank.

5. Repetition: Perform the desired number of leg lifts on one side, then switch to the other side and repeat the exercise.

The side bridge with leg lift is particularly effective for targeting the quadratus lumborum because it challenges this muscle to stabilize the pelvis and spine laterally while also resisting the downward pull of gravity. Strengthening the QL with this exercise helps improve lateral stability, reduce lower back pain, and enhance core strength, especially during activities that involve side bending or lifting. Regularly incorporating this exercise into your routine can lead to a stronger, more resilient lower back and better overall functional movement.

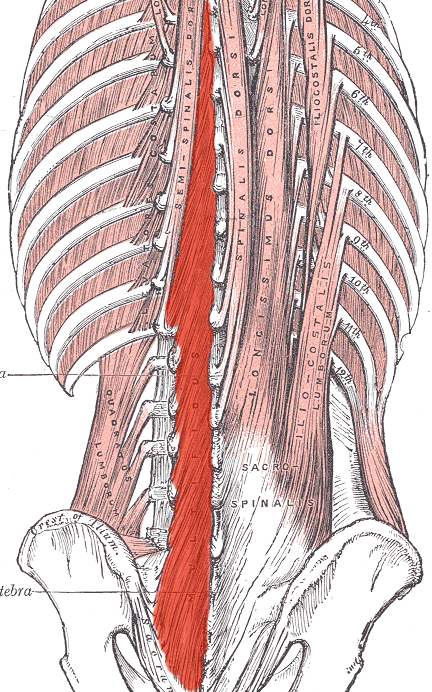

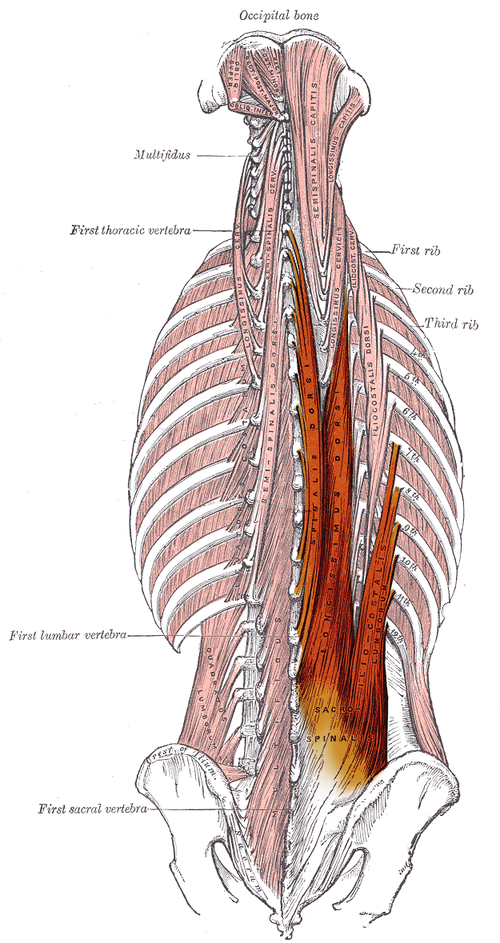

Multifidus

The multifidus is a deep spinal muscle that plays a critical role in stabilizing the vertebrae and maintaining proper posture. Located along the spine, the multifidus runs from the sacrum (at the base of the spine) to the cervical vertebrae (neck), attaching to the spinous processes of each vertebra. Unlike larger, more superficial back muscles, the multifidus consists of many small, segmented muscles that provide fine-tuned control of spinal movement and stability. Its primary function is to stabilize the spine during movement by preventing excessive motion between individual vertebrae, which is crucial for protecting the spinal column from injury. The multifidus works continuously, even during simple activities like sitting or standing, to maintain an upright posture and support the alignment of the spine. Despite its importance, the multifidus is often underdeveloped in people with back pain, as it can weaken due to inactivity or improper movement patterns. Strengthening the multifidus through targeted exercises, such as bird-dogs, quadruped extensions, and exercises that challenge core stability, is essential for improving spinal health, reducing the risk of back pain, and enhancing overall functional movement. By maintaining a strong and active multifidus, individuals can achieve better posture, more effective movement patterns, and a reduced likelihood of lower back injuries.

An effective exercise that specifically targets the multifidus is the Bird-Dog exercise. Here’s how to perform it:

1. Starting Position: Begin on your hands and knees in a tabletop position, with your hands directly under your shoulders and your knees under your hips. Keep your spine neutral and engage your core muscles to maintain stability.

2. Movement: Simultaneously extend your right arm forward and your left leg backward, ensuring that both limbs remain parallel to the ground. Focus on keeping your hips level and your spine stable throughout the movement, avoiding any excessive arching or twisting.

3. Contraction: As you extend your arm and leg, concentrate on engaging the multifidus muscles along your spine to stabilize your torso. Hold the extended position for a moment, feeling the contraction in the multifidus.

4. Return: Slowly bring your arm and leg back to the starting position, maintaining control and stability in your core.

5. Repetition: Perform the exercise on the opposite side, extending your left arm and right leg. Alternate sides for the desired number of repetitions.

The bird-dog exercise is particularly effective for targeting the multifidus because it requires spinal stability and controlled movement, which directly engages these deep back muscles. The multifidus muscles play a critical role in maintaining spinal alignment and controlling small, stabilizing movements of the vertebrae. Regularly incorporating the bird-dog into your exercise routine can help improve spinal stability, reduce the risk of lower back pain, and enhance overall core strength and balance.

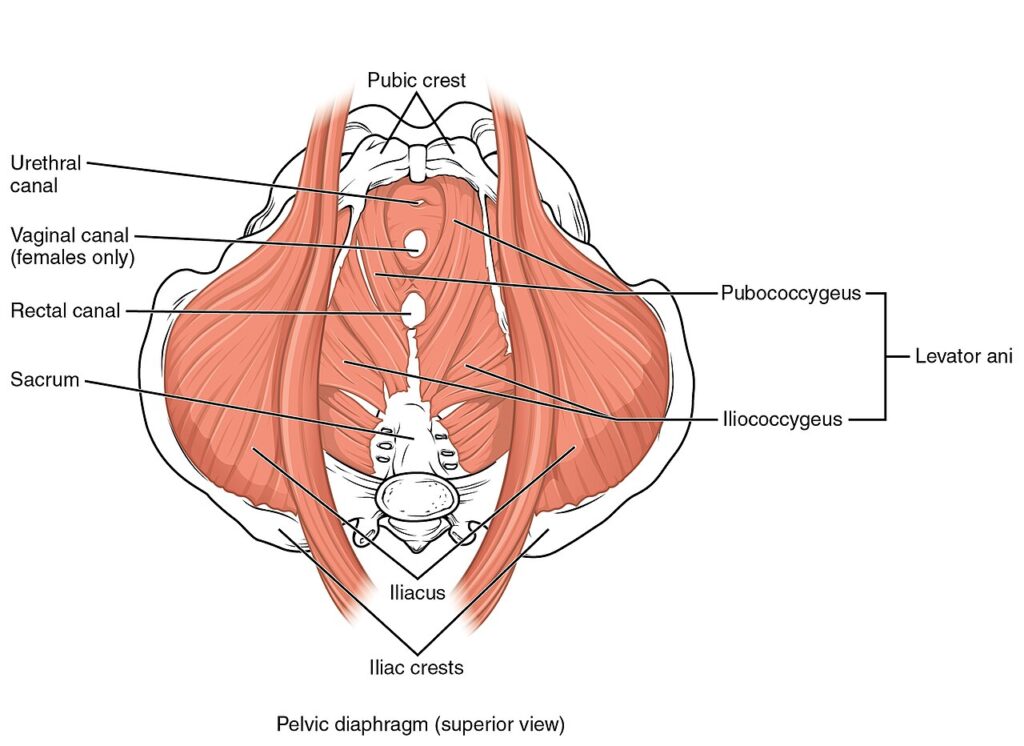

Pelvic Floor Muscles

The pelvic floor muscles are a group of muscles located at the base of the pelvis, forming a hammock-like structure that supports the pelvic organs, including the bladder, intestines, and, in women, the uterus. These muscles play a crucial role in core stability, urinary and bowel control, sexual function, and maintaining proper posture. The pelvic floor muscles work in coordination with the deep abdominal muscles, diaphragm, and lower back muscles to stabilize the pelvis and spine during movement and activities such as lifting, running, and jumping. Despite their importance, pelvic floor muscles are often overlooked in fitness routines, which can lead to weakness, particularly in individuals who have undergone pregnancy, surgery, or those who lead a sedentary lifestyle. Weak pelvic floor muscles can contribute to issues such as urinary incontinence, pelvic organ prolapse, and lower back pain. Strengthening the pelvic floor through targeted exercises, such as Kegels, pelvic tilts, and exercises that engage the deep core, is essential for maintaining pelvic health, improving core strength, and enhancing overall functional fitness. By incorporating pelvic floor training into regular exercise routines, individuals can prevent or alleviate pelvic floor dysfunction, support better posture, and improve overall well-being.

An effective exercise that specifically targets the pelvic floor muscles is the Kegel Exercise. Here’s how to perform it:

1. Starting Position: You can perform Kegel exercises in various positions, such as lying down, sitting, or standing. Choose a comfortable position where you can relax your body, particularly your abdominal and thigh muscles.

2. Identification: Before starting, identify your pelvic floor muscles by attempting to stop the flow of urine midstream when you’re using the bathroom. The muscles you use to do this are your pelvic floor muscles. Do not perform the Kegel exercise during urination regularly, as this can lead to incomplete bladder emptying and urinary issues.

3. Movement (Contraction): Once you’ve identified your pelvic floor muscles, contract them by imagining that you are trying to lift or squeeze the muscles upward, as if you were stopping the flow of urine or holding in gas. Make sure to only engage the pelvic floor muscles, keeping your abdominal, gluteal, and thigh muscles relaxed.

4. Hold: Hold the contraction for about 3 to 5 seconds, focusing on maintaining the tension in your pelvic floor muscles without involving other muscle groups.

5. Release: Slowly relax the pelvic floor muscles, completely releasing the contraction for about 3 to 5 seconds before repeating.

6. Repetition: Perform 10 to 15 repetitions in one session, aiming to do Kegel exercises multiple times a day. As your strength improves, you can gradually increase the duration of the hold to 10 seconds.

The Kegel exercise is particularly effective for strengthening the pelvic floor muscles, which support the bladder, uterus, and bowel, and play a crucial role in urinary and bowel control, sexual function, and overall core stability. Strengthening these muscles through regular Kegel exercises can help prevent or alleviate issues such as urinary incontinence, pelvic organ prolapse, and improve sexual health. For both men and women, consistently practicing Kegel exercises is key to maintaining pelvic floor health and enhancing overall well-being.

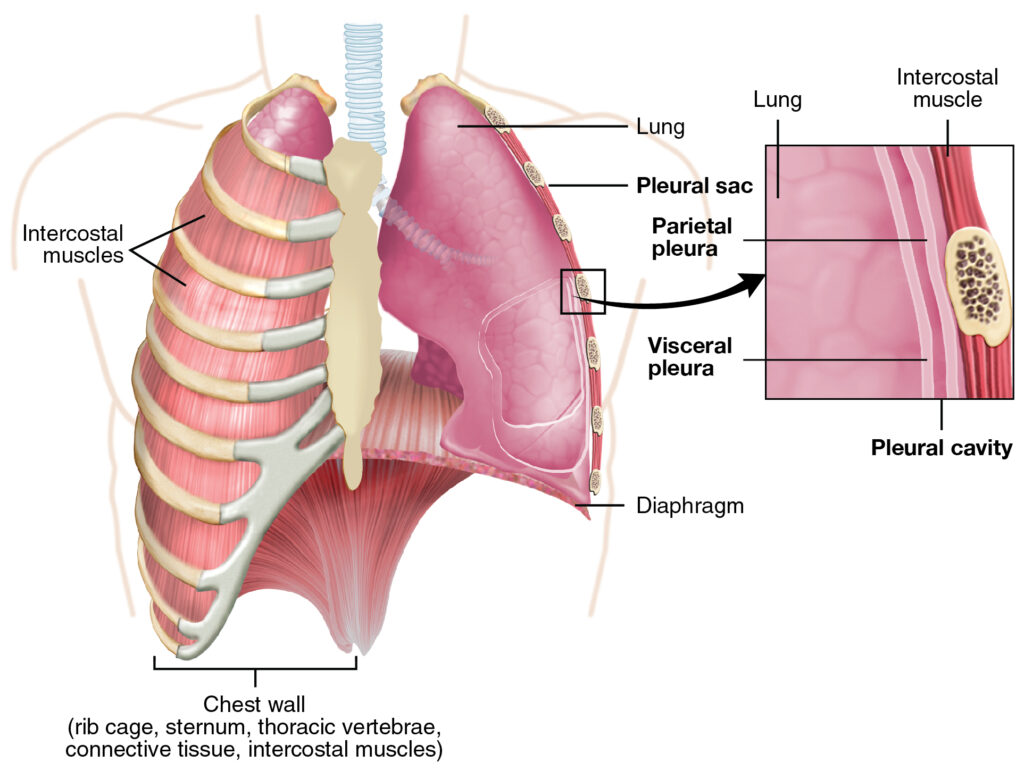

Diaphragm

The diaphragm is a dome-shaped muscle located just below the lungs and heart, playing a vital role in the respiratory process. It separates the thoracic cavity, which houses the lungs and heart, from the abdominal cavity. As the primary muscle of respiration, the diaphragm contracts and flattens when you inhale, creating a vacuum that allows air to be drawn into the lungs. During exhalation, the diaphragm relaxes and returns to its dome shape, pushing air out of the lungs. Beyond its critical role in breathing, the diaphragm also contributes to core stability by working in tandem with the abdominal muscles, pelvic floor, and lower back muscles to maintain intra-abdominal pressure, which supports the spine and internal organs during physical activity. Despite its importance, the diaphragm is often overlooked in discussions of core and respiratory health, with many people relying on shallow chest breathing rather than deep diaphragmatic breathing. Proper diaphragm function is essential for efficient oxygen intake, stress reduction, and maintaining a strong, stable core. Strengthening and training the diaphragm through practices such as deep breathing exercises, yoga, and diaphragmatic breathing techniques can enhance respiratory efficiency, improve posture, reduce tension in the upper body, and support overall physical and mental well-being.

An effective exercise that specifically targets the diaphragm is Diaphragmatic Breathing (Deep Belly Breathing). Here’s how to perform it:

1. Starting Position: You can perform diaphragmatic breathing while lying on your back with your knees bent and feet flat on the floor, sitting in a chair with your back straight, or even standing. Place one hand on your chest and the other on your abdomen, just below your ribcage.

2. Movement (Inhalation): Slowly inhale deeply through your nose, allowing your abdomen to rise as your diaphragm contracts and moves downward. Focus on filling your lungs fully by expanding your belly outward, rather than lifting your chest. Your hand on your abdomen should rise while the hand on your chest remains relatively still.

3. Contraction: Hold the inhaled breath for a second or two, allowing your diaphragm to fully engage and your lungs to fill completely.

4. Exhalation: Exhale slowly and fully through your mouth, gently contracting your abdominal muscles to push the air out. As you exhale, your diaphragm will relax and move upward, helping to expel air from your lungs. Your abdomen should fall back down during this process.

5. Repetition: Continue this controlled breathing pattern for several minutes, focusing on slow, deep breaths that fully engage the diaphragm with each inhalation and exhalation.

Diaphragmatic breathing is particularly effective for strengthening the diaphragm because it encourages full lung expansion and optimal air exchange, which helps to train and tone the diaphragm muscle. This exercise is beneficial for improving respiratory efficiency, reducing stress, enhancing core stability, and promoting relaxation. Diaphragmatic breathing is often used in respiratory therapy, stress management, and athletic training to improve breathing mechanics and overall lung function. Regular practice of this technique can lead to better control over your breathing, enhanced oxygen delivery to your body, and greater overall well-being.

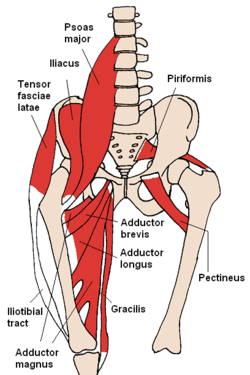

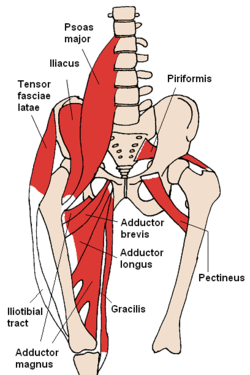

Psoas Major

The psoas major is a deep-seated core muscle that plays a critical role in connecting the upper and lower body, influencing both movement and posture. Originating from the lumbar vertebrae (T12 to L5), it runs down through the pelvis and inserts into the lesser trochanter of the femur (thigh bone). As the primary hip flexor, the psoas major is responsible for lifting the thigh toward the torso, a movement essential for activities such as walking, running, and climbing stairs. Additionally, the psoas major contributes to stabilizing the spine and pelvis, particularly during dynamic movements or when maintaining an upright posture. Because of its deep location and complex role, the psoas major is often overlooked or misunderstood in traditional fitness routines, leading to imbalances that can cause lower back pain, hip tightness, and postural issues. Prolonged sitting, for example, can lead to a shortened and tight psoas major, exacerbating these problems. Strengthening and stretching the psoas major through targeted exercises, such as leg lifts, lunges, and hip flexor stretches, is crucial for maintaining hip flexibility, improving core stability, and preventing lower back and pelvic discomfort. A well-conditioned psoas major enhances overall mobility, supports better posture, and contributes to a balanced, pain-free movement.

An effective exercise that specifically targets the **psoas major** is the **Standing Hip Flexor March**. Here’s how to perform it:

1. Starting Position: Stand upright with your feet hip-width apart. Engage your core to maintain a neutral spine, and keep your shoulders relaxed. If balance is a concern, you can perform this exercise near a wall or chair for support.

2. Movement (Hip Flexion): Begin by lifting your right knee toward your chest, aiming to bring your thigh parallel to the ground. As you lift, focus on engaging the psoas major, which is responsible for hip flexion. Your left leg should remain straight and stable.

3. Contraction: Hold the lifted position for 2-3 seconds, keeping your core tight and your pelvis neutral. You should feel the psoas major working to maintain the position.

4. Return: Slowly lower your right leg back to the starting position, maintaining control over the movement.

5. Repetition: Repeat the movement with your left leg, alternating sides. Perform the desired number of repetitions on each leg, ensuring that each lift is slow and controlled.

The standing hip flexor march is particularly effective for isolating the psoas major because it emphasizes the hip flexion movement, which is the primary function of this muscle. Strengthening the psoas major can improve hip stability, enhance overall core strength, and support better posture and lower back health. This exercise is beneficial for athletes and anyone looking to improve hip mobility and strength, as a strong psoas major contributes to more efficient and powerful lower body movements.

Iliacus

The iliacus is a vital muscle in the hip region, closely associated with the psoas major, together forming the iliopsoas, which is the primary hip flexor. The iliacus originates from the inner surface of the iliac bone (the large pelvic bone) and the sacrum, and it inserts into the lesser trochanter of the femur, merging with the tendon of the psoas major. Its primary function is to flex the thigh at the hip joint, bringing the leg toward the torso, an action fundamental to walking, running, and other lower body movements. Additionally, the iliacus plays a significant role in stabilizing the pelvis during movement and maintaining proper posture. Despite its importance, the iliacus is often overlooked in exercise routines, leading to tightness or weakness, especially in individuals who spend a lot of time sitting. This can result in hip stiffness, lower back pain, and compromised mobility. Targeting the iliacus through stretching and strengthening exercises, such as lunges, leg raises, and hip flexor stretches, is essential for ensuring hip flexibility, improving lower body strength, and supporting overall pelvic stability. A well-conditioned iliacus contributes to more fluid and pain-free movement, enhancing both athletic performance and everyday activities.

An effective exercise that specifically targets the **iliacus** muscle is the **Seated Leg Lift**. Here’s how to perform it:

1. **Starting Position**: Sit on the edge of a chair or bench with your feet flat on the floor and your back straight. Place your hands on the sides of the chair for support, keeping your core engaged to maintain a neutral spine.

2. **Movement (Leg Lift)**: Slowly lift your right knee toward your chest, keeping your back straight and avoiding any leaning backward. Focus on using the iliacus muscle to lift your thigh. Your hip should flex while your lower leg remains relaxed and your foot lifts off the ground.

3. **Contraction**: Hold the lifted position for 2-3 seconds, fully engaging the iliacus as you maintain the position. Your core should stay engaged to support your spine.

4. **Return**: Slowly lower your leg back to the starting position with control, ensuring that your movement is steady and focused.

5. **Repetition**: Repeat the movement with your left leg, alternating sides. Perform the desired number of repetitions on each leg.

The seated leg lift is particularly effective for isolating the iliacus because it focuses on the hip flexion movement, where the iliacus is most active. Strengthening the iliacus helps improve hip stability, enhances core strength, and contributes to better posture and lower back support. This exercise is especially beneficial for those who spend long periods sitting or who want to improve their hip flexibility and strength. Regularly incorporating seated leg lifts into your routine can help maintain a healthy and functional iliacus, supporting overall lower body movement and stability.

Obliquus Capitis

The obliquus capitis muscles, comprising the obliquus capitis superior and obliquus capitis inferior, are small but crucial muscles located at the base of the skull, forming part of the suboccipital group. These muscles play an essential role in head movement and neck stability. The obliquus capitis superior originates from the transverse process of the atlas (the first cervical vertebra) and inserts into the occipital bone of the skull. It primarily assists in tilting the head to the side and extending it backward. The obliquus capitis inferior, originating from the spinous process of the axis (the second cervical vertebra) and inserting into the transverse process of the atlas, is responsible for rotating the head to the same side. Despite their small size, these muscles are critical for fine motor control of the head and neck, allowing for precise movements and contributing to overall postural alignment. However, they are often neglected in both strength training and stretching routines, which can lead to stiffness, tension headaches, and neck pain, particularly in those who spend long hours in front of computers or looking down at devices. Regularly stretching and strengthening the obliquus capitis muscles can help maintain neck flexibility, reduce tension, and support healthy head and neck posture, which is essential for preventing discomfort and enhancing overall well-being.

Inferior

The obliquus capitis inferior is a small but important muscle located at the base of the skull, playing a key role in head and neck movement. Unlike its counterpart, the obliquus capitis superior, this muscle does not attach directly to the skull. Instead, it originates from the spinous process of the axis (C2), the second cervical vertebra, and inserts into the transverse process of the atlas (C1), the first cervical vertebra. The primary function of the obliquus capitis inferior is to rotate the head to the same side, allowing for precise and controlled head movements. It is also involved in stabilizing the atlantoaxial joint, which is crucial for the rotation of the head. Despite its small size, the obliquus capitis inferior plays a significant role in maintaining neck stability and ensuring smooth, pain-free head movements. This muscle is often overlooked in typical exercise routines, which can lead to stiffness and imbalances in the neck, contributing to tension headaches and discomfort, especially in individuals who spend extended periods in static positions, such as sitting at a desk. Targeted exercises and stretches for the obliquus capitis inferior can help maintain neck mobility, reduce tension, and support overall cervical spine health, preventing pain and enhancing daily functional movements.